Dean’s article also caught my attention because I’d spent much of the previous few years reporting on moral damage, interviewing morally compromised workers in menial occupations. I interviewed prison guards who patrol violent prisons, undocumented immigrants toil in industrial slaughterhouse “slaughterhouses,” and workers on offshore rigs in the fossil fuel industry. Many of these workers prefer not to be talked about or identified because they know they can easily be replaced by others. Physicians are privileged compared to them, earning six-figure salaries and holding prestigious jobs that free them from the drudgery endured by many other members of the workforce, including nurses and caretakers in the healthcare industry. But in recent years, despite the esteem of their profession, many doctors have found themselves subject to practices more common with manual laborers in auto factories and Amazon warehouses, such as tracking their productivity by the hour, and under pressure from management Work faster.

Because doctors are highly skilled professionals and not easily replaceable, I don’t think they would be as reluctant to discuss the distressing conditions of their jobs as the low-wage workers I interviewed. But none of the doctors I contacted dared to speak publicly. “I’ve since reconsidered this and don’t think it’s something I can do now,” one doctor wrote me. “Need to be ASAP,” another text message said. Some of the sources I tried to contact signed non-disclosure agreements barring them from speaking to the media without permission. Others worry that if they anger their employers, they could be disciplined or fired, a fear that appears to be amply borne out by the growing number of health care systems being taken over by private equity firms. In March 2020, an emergency room doctor named Lin Ming was removed from his hospital’s rotation after expressing concerns about his Covid-19 safety protocols. Lin works at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash., but his actual employer is TeamHealth, a unit of the Blackstone Group.

As more and more hospitals outsource emergency department staff to cut costs, emergency physicians find themselves at the forefront of these trends. A 2013 study by Robert McNamara, chair of the emergency medicine department at Temple University in Philadelphia, found that 62 percent of emergency physicians in the United States could be fired without due process. Nearly 20 percent of the 389 ER physicians surveyed said they had been threatened for raising care quality issues and forced to make decisions based on financial considerations that could be detrimental to those they care for, such as being forced to Patients opting out of Medicare and Medicaid may be encouraged to take more testing than is necessary. In another study, more than 70% of emergency physicians agreed that corporatization of their field had negatively or strongly negatively affected the quality of care and their own job satisfaction.

Of course, there are plenty of doctors who love what they do and don’t feel the need to speak up. Clinicians in high-paying specialties like orthopedics and plastic surgery “are doing great, thank you,” joked a doctor I know. But a growing number of doctors have come to believe that the pandemic is only exacerbating the strain on an already failing health care system that prioritizes profits over patient care. They note how the emphasis on the bottom line often puts them in a moral bind, especially as young doctors are contemplating how to resist. Some are considering whether these sacrifices and compromises are worth it. “I think a lot of doctors feel like there’s something that’s bothering them, something deep inside them that they’re committed to,” Dean said. She notes that the term “moral injury” was originally coined by psychiatrist Jonathan Shay to describe the wound that forms when a person’s sense of what is right is betrayed by a leader in a high-stakes situation. “Clinicians not only feel betrayed by their leaders,” she says, “but when they let these barriers get in their way, they are part of the betrayal. They are the tools of the betrayal.”

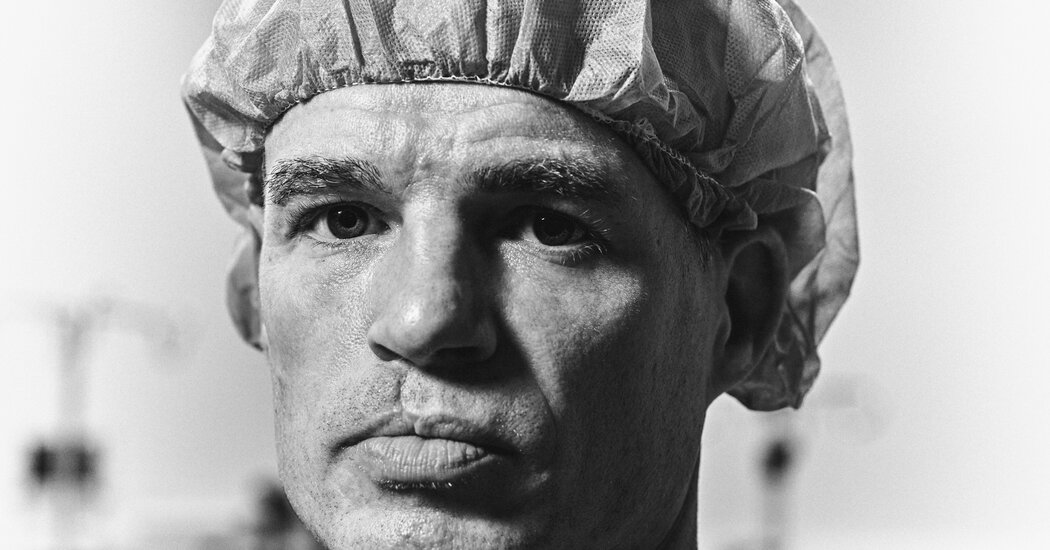

Not long ago, I spoke to an emergency physician (I’ll call her A.) about her experience. (She did not wish to use her name, explaining that she knew several doctors who had been fired for voicing concerns about poor working conditions or patient safety issues.) A., a soft-spoken and soft-mannered woman, offered Arriving at the ER as a “sacred space,” she loves working in this place because she can have a profound impact on the lives of her patients, even those who can’t make it through. During her training, a terminally ill patient told her somberly that his daughter would not be able to make it to the hospital to be with him in his final moments. A. Assure the patient that he will not die alone, then hold his hand until he passes away. Interactions like this, she told me, are impossible today because of the new focus on speed, efficiency, and relative value units (RVU), a metric used to measure physician reimbursement that some feel rewards physicians for testing and procedures, and discourage them from spending too much time on lower-paying tasks, such as listening and talking to patients. “It’s all about RVU and being faster,” she says of the ethos that permeates the practice she’s been working in. “The time from your door to the doctor, the time from your room to the doctor, the time from your initial assessment to discharge.”