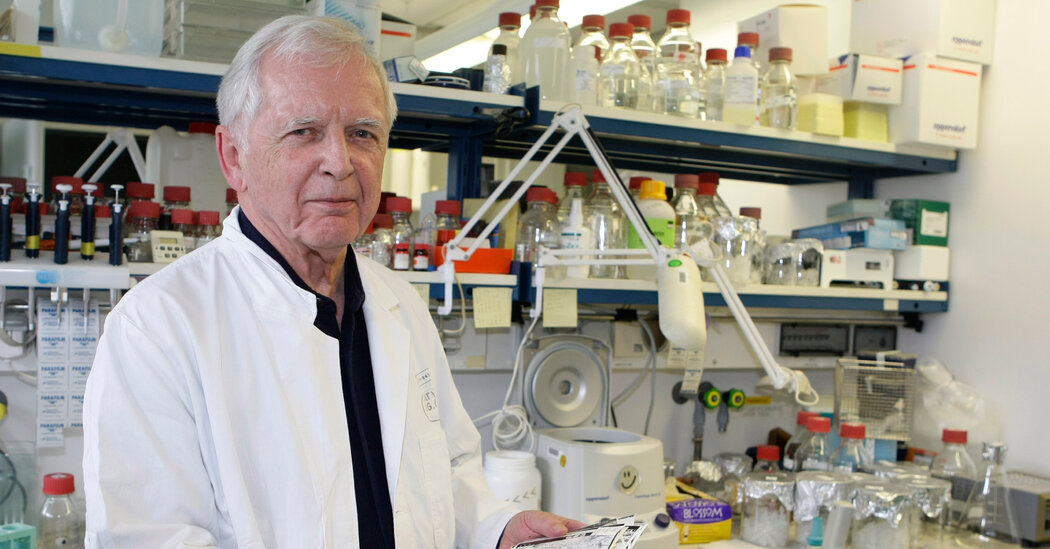

German virologist Dr Harald zur Hausen, who won the 2008 Nobel Prize in Medicine for discovering that the seemingly benign human papillomavirus, known to cause warts, also causes cervical cancer, at his home in Heidelberg, Germany, on May 29 died. He is 87 years old.

His death was announced at the German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg, which Dr. zur Hausen headed for 20 years. Dr. zur Hausen suffered a stroke in May, said Josef Puchta, the center’s former administrative director and longtime colleague and friend.

Dr. zur Hausen’s discovery paved the way for a vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted disease that can also cause other cancers, including those of the vagina, vulva, penis, anus and the back of the throat.

According to the National Cancer Institute, more than 600,000 people develop HPV-related cancers each year. Up to 90% of cancers can be prevented by vaccination.

Dr. Zurhausen left a “huge legacy,” Dr. Margaret Stanley, an HPV researcher at the University of Cambridge, said in an interview: A life-saving vaccine and a life-saving test can detect the virus.

Colleagues remember Dr. zur Hausen as courteous, thoughtful, and respectful—which, they point out, was not always the case in reputable research laboratories—and more than one person called him a “gentleman.”

Timo Bund, a scientist at the German Cancer Research Center, said he is doggedly committed to his research and can be “firm” when he has an idea. Dr. Bund said Dr. zur Hausen’s hypothesis that HPV causes cervical cancer contradicted the prevailing wisdom of “virtually the entire scientific community” and took him a decade to prove.

When he first proposed the concept in the 1970s, many scientists believed that cervical cancer was caused by Herpes simplex virus. But Dr. zur Hausen found no signs of herpes in biopsies of patients with cervical cancer. When he presented the results at a scientific meeting in 1974, he received “strong criticism,” he recalls in an autobiographical essay in the Annual Review of Virology.

Dr. zur Hausen was intrigued by reports that genital warts could, in rare cases, turn into cancer. He began looking for human papillomavirus DNA in the cells of cervical cancer patients using a gene probe, a short piece of single-stranded DNA designed to bind to a specific sequence in the HPV genome.

The work proved challenging, in part because it was clear that there are many different types of HPV, each with its own genetic sequence, and not all of them cause cancer.

Dr Zurhausen is not intimidated. “I don’t think he ever doubted that it was right in any way,” says geneticist Michael Boschart, a Ph.D. at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. students in the research group.

Finally, in 1983, Dr. zur Hausen and his colleagues announced that they had discovered a new type of HPV in cervical cancer cells. The next year, they reported another one. They found that about 70 percent of cervical cancer biopsies contained one of these two viruses.

Other scientists quickly confirmed the discovery. “I’m somewhat pleased with this situation, because several colleagues have been scoffing at our research so far, saying, ‘Everyone knows that warts and papillomaviruses are harmless,'” Dr. zur Hausen in the In the Annual Review of Virology.

Dr. zur Hausen freely shared the clone of the viral DNA with other researchers. “Most scientists are selfish, they stick to their stuff,” Dr. Stanley said. “Because he’s handing them over to the papillomavirus community, there’s been an absolute surge in workload.”

The research could help accelerate scientific understanding of the virus and the development of a vaccine. The first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, two years after Dr. zur Hausen shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with the two French virologists who discovered HIV, Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier (who died in February).

He became an ardent advocate of the vaccine, which is so effective that many children do not get it. He argues that the vaccine, which was originally intended primarily for girls, should also be given to boys, and health officials now recommend the same.

Harald zur Hausen was born on March 11, 1936 in Gelsenkirchen, Germany, the youngest of four children of Melanie and Eduard zur Hausen. His father was an officer in the German Army.

The industrial area where he grew up was heavily bombed in World War II. “As a result, all schools were closed in early 1943, which was obviously not conducive to education, but was popular with many children,” recalls Dr. Zurhausen. He has been back in school for almost two years.

He decided to study medicine, obtained his degree at the University of Düsseldorf in 1960, and became interested in the origins of cancer. His itinerant research career took him to several years at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and then to various German universities. In the 1960s and early 1970s, he conducted research on the Epstein-Barr virus and lymphoma.

In 1972 he moved to the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and started his work on cervical cancer. He later continued this work at the University of Freiburg.

It was at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg that he met the biologist Ethel-Michele de Villiers, who later became his wife and close scientific collaborator.

Dr. zur Hausen wrote in the Annual Review of Virology that no one had “more influence on my personal life and scientific career”. “She repeatedly said wryly that the two of us divided our activities: she did the work and I did the talking. Indeed, a wealth of experimental data acquired over decades and many excellent ideas are hers. See her work and Her intellectual input and advice is often underestimated by several of her colleagues, and I think she is right to say so.”

She is survived by her three sons, Jan Dirk, Axel and Gerrit, from his previous marriage. Friends and colleagues said they knew next to nothing about the marriage, noting that Dr Zurhausen was a deeply private man.

He became Scientific Director of the German Cancer Research Center in 1983, a position he held until 2003. But he never stopped researching, and in recent years he has turned his attention to breast cancer, colon cancer and other cancers.

“He retired from his directorship,” Dr. Puchta said, “but not from his science.”